Deception: The Art of Intelligence

- Aleksander Traks

- Jan 20, 2025

- 2 min read

Kong Ming is an inspirational character in Romance of the Three Kingdoms. His exploits—how he tricked an army ten times his size by opening city gates and playing the lute, or how he sent out boats filled with straw to collect Cao Cao’s arrows—are phenomenal. A war in the Three Kingdoms was often won through plots and deception, as Sun Tzu teaches, rather than feats of strength like those celebrated in the Germanic Nibelungenlied.

But why care about it? Isn’t it some dystopian lifestyle comparable to Gordon Gekko’s (even though I love his speech on greed). Deception and trickery might not be the noblest pursuits, but in situations rife with conflict, knowledge and a good plot can save many lives. In a similar vein, Machiavelli teaches us that while we do want to be loved, if that’s not possible, we might have to choose to be feared.

Deception vs. Direct Conflict

History shows that direct conflict often destabilizes both sides, like a civil war in Africa. Such wars rarely help either the rebels or the people in power in the long term and instead bring widespread devastation. In contrast, strategic diplomacy—sometimes involving clever misdirection—can lead to more favorable outcomes with fewer costs.

A historical parallel can be drawn from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, where Diao Chan’s cunning plot to drive a wedge between Dong Zhuo and Lü Bu led to the downfall of a tyrant. Her actions, though deceptive, served a greater purpose.

The Allure and Risks of Deceptive Characters

There is a certain attraction to characters of a deceptive nature or those who plot, such as Cesare Borgia or the brilliant tacticians of Chinese history. Their intellect and cunning are undeniably captivating. Yet in reality, such traits often come at a cost.

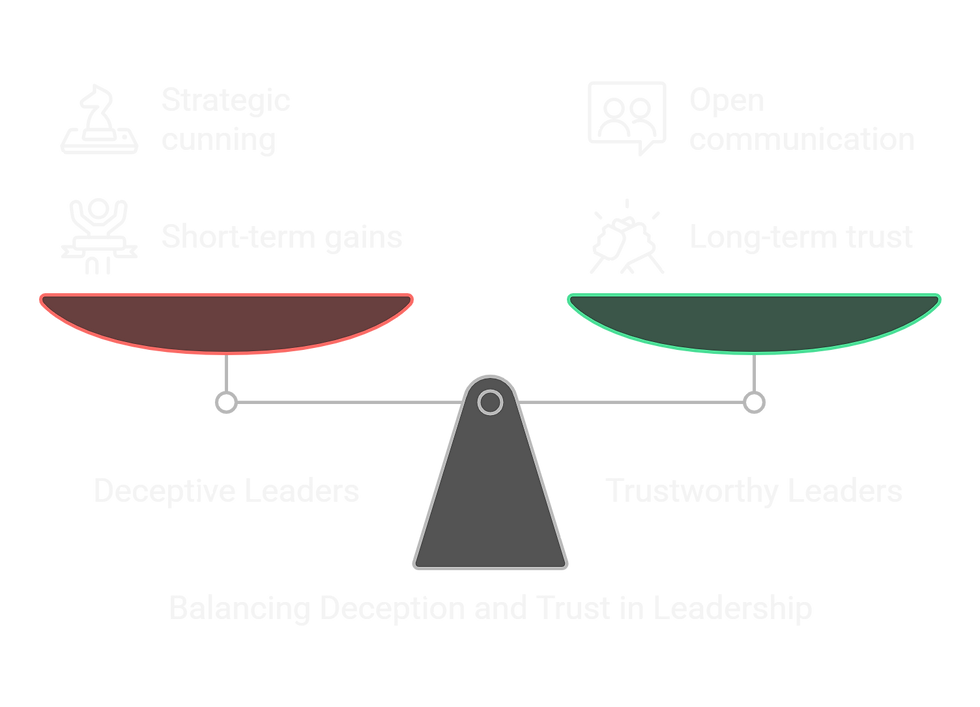

In the business world or politics, leaders who rely on deception are rarely trusted. Historical examples, like certain leaders in Vietnam who met untimely ends after being perceived as duplicitous, remind us that deception can make one a target. Barry Lyndon’s downfall in fiction or Cao Cao’s inability to claim the throne despite his ambitions underscores this truth: deception may win battles, but it often loses the war.

Conclusion

Deception, while fascinating and sometimes effective, is a double-edged sword. It may secure short-term wins, but trust and integrity are what sustain lasting leadership. The stories of Kong Ming and Diao Chan remind us that cleverness alone cannot build enduring legacies.

Comments